Different types of editing

Did you think writing the book was the hard part? Oh, my sweet summer child. Experienced authors can probably write a pretty decent first draft, but for the rest of us, the first draft is just a pile of word vomit. It’s bad. And now you have to fix it. How? By editing the shit out of that monster.

The dreaded self-edit

So you wrote a pile of word vomit? Good for you! Now it’s time to whip that bad boy into shape. You don’t have to do it all on your own, but you have to face the fact that this pile of world vomit is nowhere near ready to see daylight yet.

Every author handles the first self-edit differently, but there is one thing we all have in common: self-loathing and desperation. Whatever you’re feeling right now, it’s completely normal. Now stop wallowing in self-pity and get to work.

There are two ways to self-edit: while you write the first draft or afterward. Both have their pros and cons. I’m somewhere in the middle. My main focus is finishing the first draft as quickly as possible, but I do reread whatever I wrote the previous day to get back into the flow of things. You inevitably rewrite some things as you do this, so technically you are editing. I try to avoid going back further at all costs because that’s when you get lost in an endless loop of editing without actually finishing the first draft.

A much-hated but absolutely crucial part of self-editing is killing your darlings. It was William Faulkner who came up with this expression, and experienced writers have been preaching it ever since. Kill your darlings means you have to be absolutely ruthless in eliminating any scenes, side plots, characters, and words that don’t contribute to the story. I don’t care how much you slaved over that particular sentence; if it doesn’t do anything to further the plot, it must go. If you are an overwriter, this will be brutal for you. I’ve heard stories of authors deleting half their word count, but it must be done.

Sorry to kick you while you are down, but chances are you are going to need more than one self-editing round. Professional editing is crucial, but you can’t send your manuscript to agents or professional editors without polishing it to the absolute best you can. This means having your friends and family read it, enlisting beta readers, and listening to your manuscript out loud at least once.

Developmental edit

Is your manuscript in the best possible condition you can do yourself? Then it’s time to involve some professionals. The first step of getting your manuscript professionally edited is the developmental edit. Some make a distinction between developmental editing and structural editing, but I toss those into the same boat since they both focus on the story as a whole.

A developmental edit tackles all the big-picture issues. Every editor has their own style, but a developmental edit always focuses on plot, structure, characterization, pace, narrator, tense, and viewpoint.

Plot: The plot is what happens in your story, told via a sequence of events. Sometimes a story is just boring or not well-thought-out, but we writers are so invested in it, that we can’t see it. This is also the stage where plot holes are unearthed and solved.

Structure: Every story should have a structure. Which structure you end up using depends on the story itself and personal preference.

Characterization: How do your characters come across? Is it how you envisioned them to come across? Does their behavior make sense with their background and personalities? These are all questions that involve the characterization of your beloved fictional creations.

Pace: The speed at which the story unfolds. To me, the pacing is one of the most important things in a novel. I quickly lose interest, so things need to happen. There is nothing wrong with character development, but please don’t devoid pages upon pages on just character development. Throw in a few battles and a dragon or two, please.

Narrator: You, the writer, are the narrator. Regardless of which viewpoint you write from, the reader must always know who is “talking” and “feeling” all the feels. This is especially important if your story involves more than one point of view, like in Game of Thrones.

Tense: Generally speaking, there are two tenses: present and past. Yes, technically speaking, there are exceptions, but don’t bullshit me. Nobody wants to read in the future tense. It’s not “edgy” or “different”, it’s just annoying. Stick to what’s been tried and true. During a developmental edit, your editor will check if you stick with the same tense or switch back and forth.

Viewpoint: A story can be told from several viewpoints. The most common ones are first person and third person. With the third-person viewpoint, there is a distinction between third-person omniscient (all-knowing) and third-person limited. A developmental editor will check if you stay within your viewpoint. For example, a third-person limited viewpoint can’t know if the main character’s best friend is feeling jealous about her awesome quest to fight the dragon if said best friend doesn’t explicitly states or shows she is jealous.

How do I find a developmental editor?

Finding a developmental editor is highly personal. It’s also the most costly type of editing. Do compare editors against each other in both style and budget. Most editors offer a sample edit, and I definitely recommend doing this so you don’t jump in blind. Maybe you picked an editor because they did one of your favorite books, but that’s not a guarantee that you’ll click with that person. Take your time to find the right one.

Line edit

First of all: the difference between line editing and copy editing. Both focus on sentence and paragraph level, but their goal is a bit different. A line editor checks writing style and language use. A copyeditor checks the mechanics of a sentence.

When a developmental edit is all about the big picture, a line edit is about getting into the details. Your editor will check how you use language to convey your story. Things like overused words or sentences, awkward phrasing, redundancies, and unnatural dialogue have no place in your manuscript, and a good line editor will spot those from a mile away.

What’s important with line editing is that you guard your voice. While there are a lot of rules and guidelines about how a story should go, every writer has their own way of getting the message across. This is their voice. It is subjective to personal taste and “a strong voice” is highly sought after by agents. Make sure you find an editor that enhances your voice, not silence it.

Do you need a line edit?

This one is difficult to answer. If you got the money, then yes. A decent line edit will make your book better. But if you have to choose between a line edit and the other types of edits mentioned here because of budgetary restraints? Go for the other ones.

Copy edit

Now that the developmental edit and line edit took care of the story and style stuff, it’s time to get technical. The standard things a copy editor looks at are spelling, grammar, syntax, punctuation, hyphenation, and capitalization. A good copy editor does so much more: consistency, dialogue tagging and punctuation, spacing and sequencing, and formatting standard document layout.

It’s not uncommon for fantasy authors to use a different spelling of certain words to emphasize their magical abilities, such as swapping out the i for an y: witchfyre. Another classic example is using a word as a concept instead of what the word really means, like “phoners” in Stephen King’s Cell. Your copy editor doesn’t know these things, so it’s best to give them a list so they don’t accidentally correct all of your intentionally wrong-spelled words.

Do you need a copy editor?

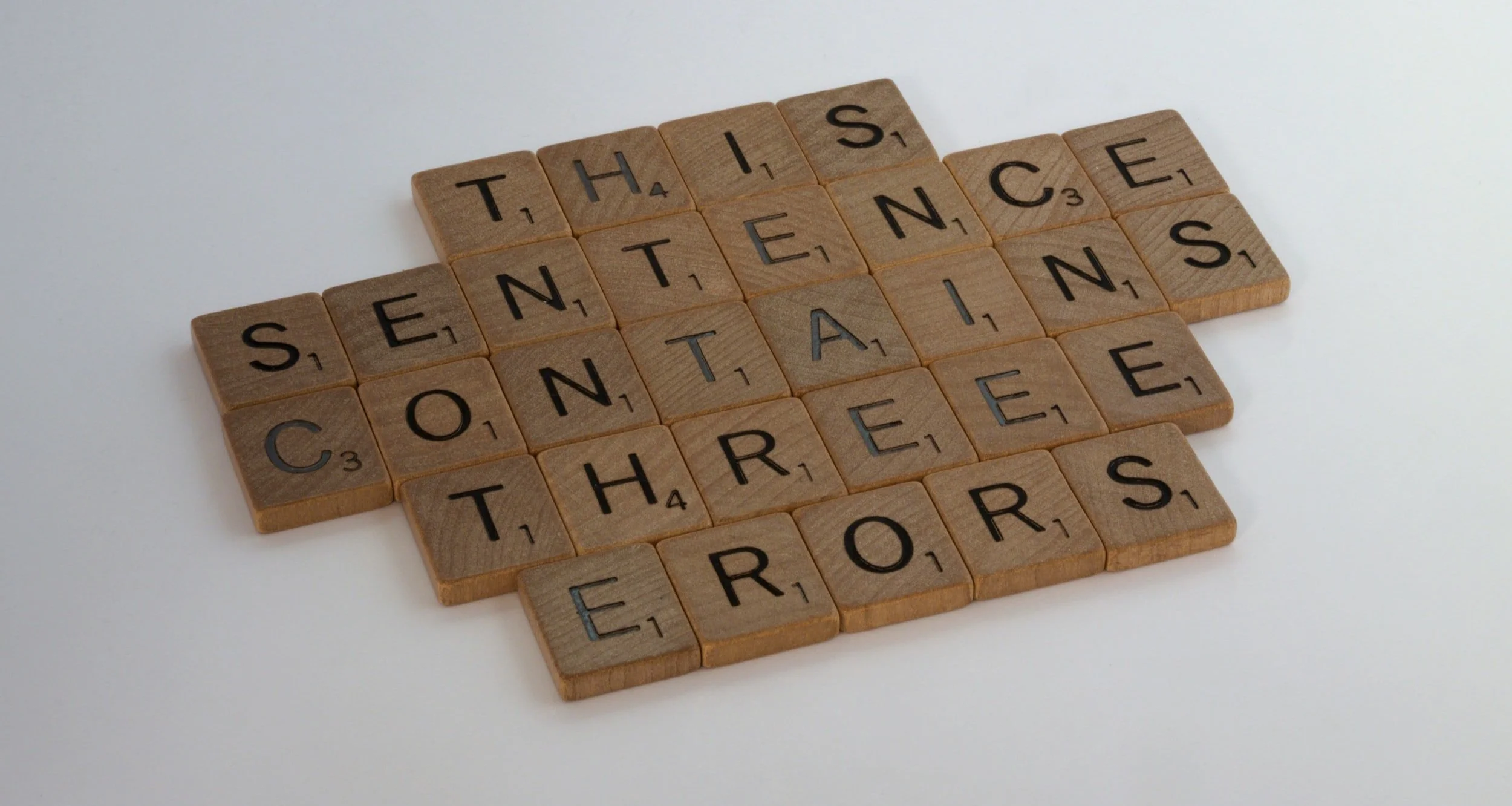

Yes, you do. There’s nothing more annoying than a book full of spelling errors, inconsistencies, and grammar mistakes. And no matter how good you are, you will make mistakes. You’ve read these words so many times by now that you’ve become blind to your own mistakes. Put another set of eyes on this and trust the process. Your readers will thank you.

Proofreading

Proofreading is the last step in the professional editing process. At this point in time, a dozen or so people will have looked at your manuscript. And there will still be mistakes. A proofreader checks every word, every letter, every comma, and every period. Not only that, but they also check spaces, margins, and overall layout. You’d be surprised at how many issues get introduced during the design stage. Does moving an image in a Word document bring back any layout nightmares?

In the best-case scenario, a proofreader hardly finds any mistakes. You might feel like it was a waste of money, but just imagine the embarrassment if those mistakes did make it into the final manuscript. With proofreading, it’s always better safe than sorry.

It is important to note that a proofreader can not replace a developmental, inline, or copy edit. Proofreading is the final check and its goal is quality control, not quality development.

Conclusion

In the world of writing, mastering the art of editing is an essential skill for producing work that truly stands out. By understanding the different types of editing and how to use them effectively, you can elevate your writing to a level of quality that will capture your readers' attention and keep them engaged.

Whether you're a seasoned pro or just starting out, it's important to know the specific goals and techniques of each type of editing, from developmental editing to proofreading, to achieve the desired outcome. With practice and perseverance, you can take your writing to new heights and create work that you're truly proud of.

So take a deep breath, grab your red pen, and get ready to transform your writing into a masterpiece. With a little bit of effort and a whole lot of passion, you can become an expert in the art of editing and craft writing that is truly unforgettable. So go forth with confidence, and let your writing soar!